4 Stages of Appendicitis: From Early Signs to Severe Pain

You’re lying in bed on a random Tuesday night when a dull ache creeps in around your belly button. Maybe it’s something you ate. Maybe it’s gas. You roll over, try to sleep it off, and hope it’ll be gone by morning.

But by dawn, the pain has moved. It’s sharper now, sitting low on your right side, and every step sends a jolt through your gut.

This is how appendicitis sneaks up on people. It doesn’t announce itself with dramatic, movie-style agony. It starts quietly before turning into one of the most common surgical emergencies in the world.

Doctors perform around 280,000 appendectomies every year in the United States alone. The condition hits roughly 7 to 8.5 percent of people at some point in their lives. And here’s what’s alarming: about 1 in 5 appendicitis cases get misdiagnosed initially, which leads to dangerous delays in treatment.

Understanding the 4 stages of appendicitis could save your life or the life of someone you love. Each stage brings different symptoms, different risks, and different levels of urgency. So let’s walk through what actually happens inside your body when your appendix decides to cause trouble.

What Exactly Is Your Appendix, and Why Does It Turn Against You?

Your appendix is a small, finger-shaped pouch that hangs off your large intestine. It sits tucked away in the lower right side of your abdomen. For a long time, doctors considered it a useless leftover from evolution. But more recent research suggests it might play a supporting role in your immune system by acting as a safe house for beneficial gut bacteria.

Here’s the irony, though. This little organ that might help protect you from infection can itself become dangerously infected.

Appendicitis happens when something blocks the opening of the appendix. Common causes include:

- A fecalith, which is basically a small, hardened piece of stool that gets stuck in the narrow tube

- Swollen lymph nodes from an infection somewhere else in your body

- Tumors, parasites, or a buildup of thick mucus, though these are less common

Once the opening is blocked, bacteria that are normally harmless start multiplying inside the trapped appendix. Pressure builds up. Blood flow drops. And from there, things go downhill fast, sometimes within 24 to 72 hours.

This isn’t a condition that gives you weeks to “wait and see.”

Acute Versus Chronic: Two Faces of the Same Problem

Before we get into the four stages, it’s worth knowing that appendicitis shows up in two very different forms.

Acute appendicitis is the one most people picture. It hits suddenly, develops over 24 to 48 hours, and causes severe symptoms that typically land you in the emergency room. It mainly affects people between the ages of 10 and 30.

Chronic appendicitis is the sneaky cousin. It develops slowly and produces milder symptoms that come and go over weeks, months, or even years. People who have it often mistake their recurring lower right abdominal discomfort for irritable bowel syndrome or general digestive trouble.

Key differences between the two:

- Acute appendicitis comes on suddenly with severe symptoms, while chronic builds gradually with recurring mild pain

- Acute is common and easier to diagnose, but chronic is rare and doctors frequently miss it

- Acute can progress to rupture within days, while chronic can flare up without warning into a full acute episode

- Both forms need an appendectomy for a permanent fix

The bottom line? Recurring abdominal pain in the lower right area deserves a proper investigation, even if it keeps going away on its own.

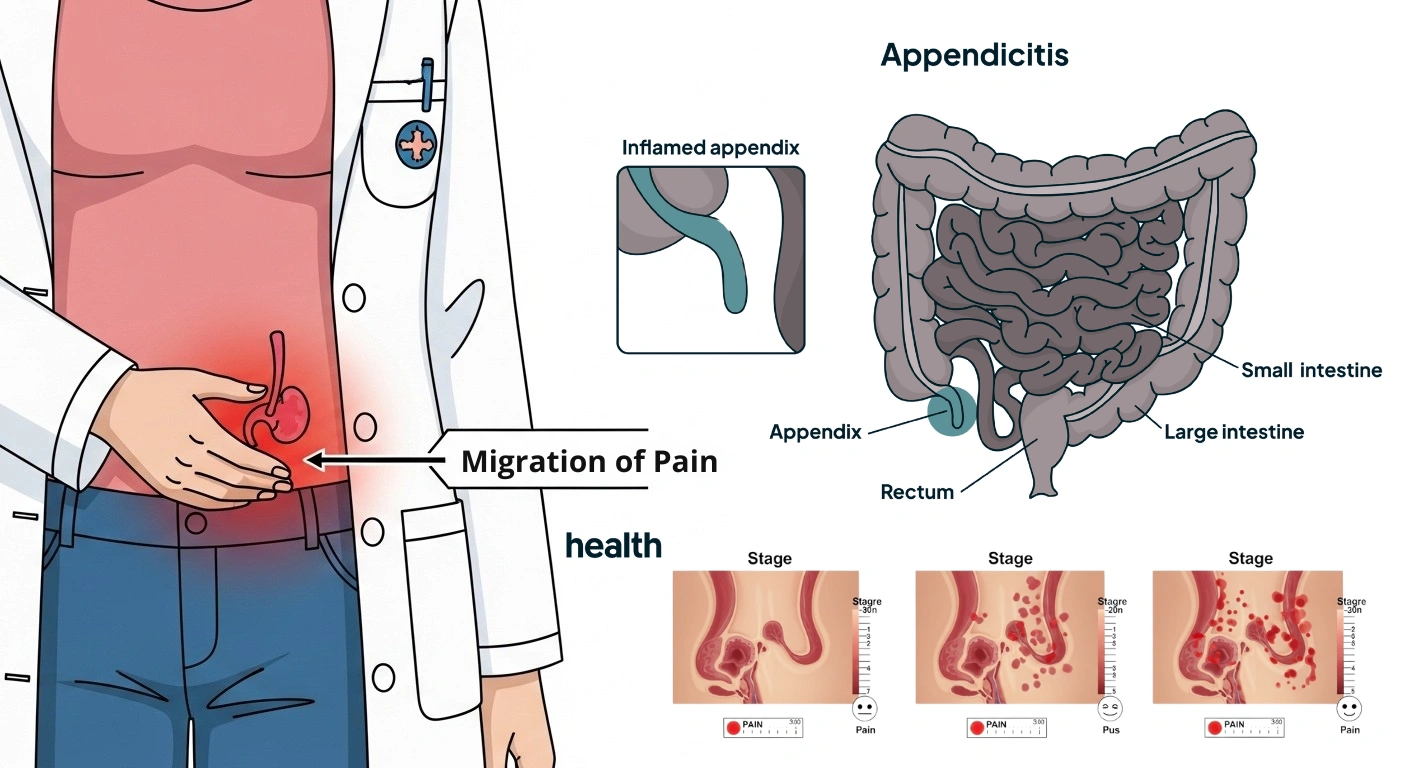

Early Inflammation The Quiet Warning

Doctors call the first stage “simple” or “early” appendicitis. It’s the trickiest stage because it doesn’t feel like an emergency. The blockage has just happened, and the appendix is starting to swell.

Mucus and fluid build up inside it. Pressure starts to rise. But the pain? It’s vague and easy to brush off.

Common symptoms at this stage:

- A dull, achy feeling around the belly button or upper abdomen

- Pain that comes and goes, feels a lot like indigestion

- Loss of appetite or mild nausea

- A low-grade fever around 99 to 100°F, or no fever at all

- Discomfort when you move, cough, walk, or ride over bumps in the car

What makes this stage so deceptive is that the pain hasn’t settled into one spot yet. The earliest pain signals travel through visceral nerve fibers, and those fibers aren’t great at pinpointing where the problem actually is. Your brain picks up “something hurts in my belly” but can’t say exactly where.

This vague pain around the navel usually lasts about four to six hours before it starts shifting.

This is the golden window. If a doctor catches it during stage one, the outcome is almost always excellent. Treatment might include antibiotics, close monitoring, or a straightforward laparoscopic appendectomy. Recovery at this stage usually takes just one to two weeks.

The catch? Most people don’t seek help because the symptoms feel manageable. They pop an antacid, blame last night’s takeout, and try to tough it out. That’s a risky move, because the clock is already ticking.

Acute Suppurative Appendicitis – When the Pain Gets Serious

If stage one goes unrecognized, the appendix moves into what doctors call the suppurative stage. “Suppurative” is just a medical way of saying “filled with pus,” and that’s exactly what’s going on inside.

White blood cells, specifically neutrophils (your body’s frontline infection fighters), flood into the appendix to battle the multiplying bacteria. The inflammation pushes through the deeper layers of the appendix wall. Small ulcers may start forming inside it.

This is when the classic symptom shift kicks in:

- Pain moves from the belly button area to the lower right abdomen, a spot doctors call McBurney’s point

- The pain gets sharper, more constant, and much harder to ignore

- Fever climbs to 102°F or higher

- Nausea and vomiting become more persistent

- Your abdomen feels tender to the touch, especially with “rebound tenderness,” which is a spike of pain when someone presses down and then lets go

- Walking, coughing, or any jarring movement makes the pain worse

At this point, antibiotics alone rarely do the job. Most patients need surgery, and sooner is better than later. The appendix hasn’t burst yet, so the operation is still relatively clean and the risk of infection after surgery stays low.

Here’s something most people don’t realize: your appendix doesn’t sit in exactly the same place as everyone else’s. Studies using 3D imaging found that the base of the appendix actually sits at McBurney’s point in only about 4 percent of people. In roughly a third of patients, it’s more than five centimeters away from that classic spot.

So the pain might not show up exactly where textbooks say it should. That’s a big reason diagnosis sometimes gets delayed, especially in pregnant women, elderly patients, or anyone whose anatomy is a little different.

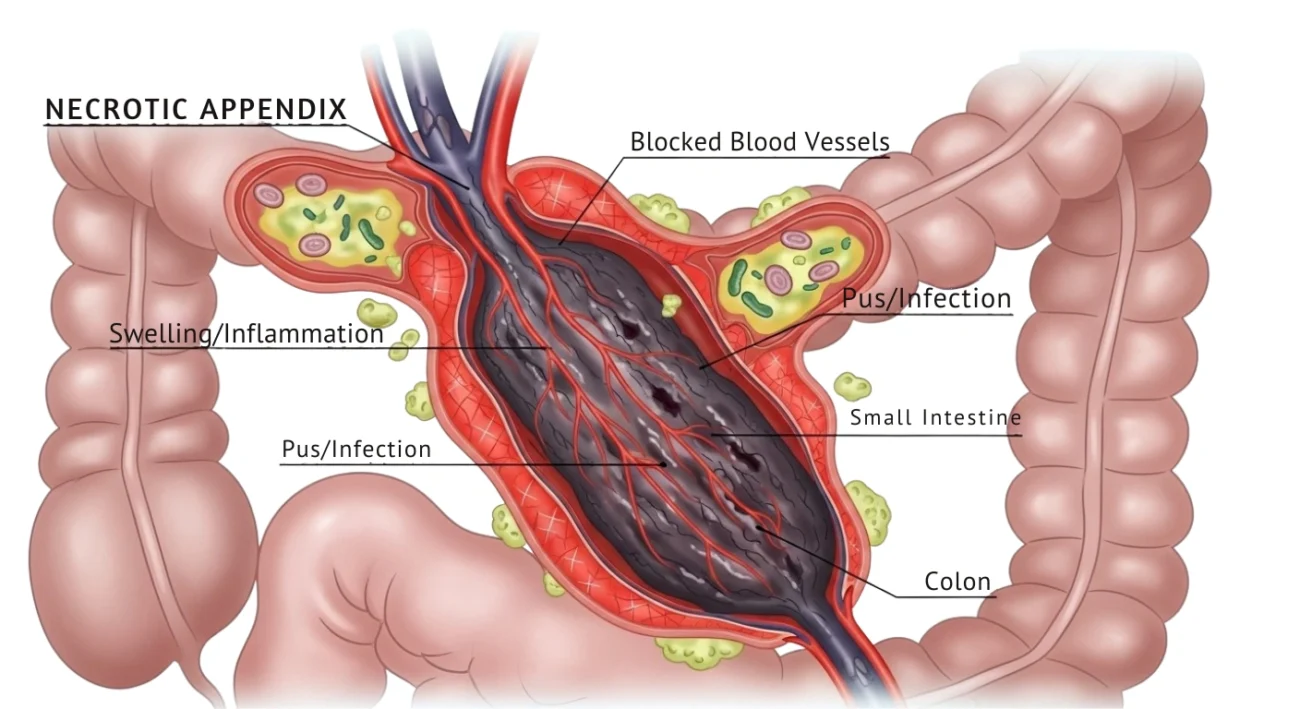

Gangrenous Appendicitis – Tissue Death and Rising Danger

If the suppurative stage goes untreated, blood flow to the appendix drops to critical levels. The constant swelling and pressure essentially choke off its blood supply. Without oxygen and nutrients, the tissue starts dying. Doctors call this process necrosis.

Once enough tissue has died, the appendix becomes gangrenous. And that’s a turning point nobody wants to reach.

A gangrenous appendix is basically a ticking time bomb. The walls are getting weaker by the hour, and a rupture could happen at any moment.

Symptoms at this stage are hard to miss:

- Excruciating pain, often in intense waves before settling into relentless throbbing

- High fever with chills, which signals a serious infection

- A rigid abdomen that’s extremely tender to touch

- Rapid heartbeat

- Paleness, weakness, and dizziness

- In some cases, a palpable mass in the abdomen where the swollen, dying appendix has grown large enough to feel through the skin

But watch out for this cruel trick. Some patients actually feel a brief moment of relief during this stage. As tissue dies, the nerve endings in the appendix wall die too, temporarily cutting down the pain signals reaching your brain. More than a few people have thought they were getting better right before things took a sharp turn for the worse.

Surgery at this stage gets more complicated. There’s a higher chance you’ll need an open appendectomy instead of the preferred laparoscopic approach. Recovery stretches to four to six weeks, and the risk of wound infections or abscess formation goes up significantly.

Perforated Appendicitis – A Full-Blown Emergency

Stage four happens when the weakened, gangrenous appendix finally gives way and bursts open. This is perforated appendicitis, and it’s a true medical emergency.

When the appendix ruptures, it dumps bacteria-laden pus and fecal matter straight into the abdominal cavity. That causes peritonitis, a widespread infection of the abdominal lining. If peritonitis isn’t treated aggressively, it can progress to sepsis, where the infection enters your bloodstream and starts shutting down organs.

Without fast, aggressive treatment, sepsis can kill.

What a ruptured appendix feels like:

- A sudden, temporary drop in pain right when the appendix bursts, because the pressure that was building up gets released

- Within hours, far worse pain that spreads across the entire abdomen

- A board-like, rigid abdomen

- Fever spiking higher than in any previous stage

- Rapid heart rate and shallow breathing

- Extreme fatigue, weakness, nausea, and vomiting

Sometimes the infection gets walled off by nearby tissues. The omentum and small bowel loops form a barrier around the ruptured appendix, creating what doctors call a phlegmon or a localized abscess. That can contain the spread temporarily, but it doesn’t solve the problem.

Treatment at this stage goes well beyond removing the appendix:

- Peritoneal lavage, where surgeons wash out the abdominal cavity to clear infectious material

- Intravenous antibiotics for several days

- Drains placed in the abdomen for ongoing fluid removal

- Extended hospital stays

- Risk of serious complications like abscess formation, intestinal obstruction, fistula development, and prolonged ileus, which is a temporary paralysis of the bowel

The overall mortality rate for appendicitis sits at about 0.28 percent globally. But that number climbs when perforation is involved, especially in elderly or immunocompromised patients. In countries with limited surgical access, appendicitis mortality ranges from 1 to 4 percent because patients tend to arrive at more advanced stages.

Appendicitis in Special Populations: Why Symptoms Don’t Always Follow the Textbook

One of the biggest reasons doctors miss appendicitis is that it simply doesn’t look the same in everyone. The “classic” pain progression works well for diagnosing healthy adults, but children, pregnant women, and elderly patients often present very differently.

How It Shows Up in Children:

Kids, especially those under five, can’t always explain what they’re feeling. A toddler isn’t going to tell you the pain moved to their lower right side.

What parents should watch for instead:

- Unusual irritability and refusing to eat

- Being unusually tired or not wanting to walk or move around

- Belly pain that seems spread out rather than focused on one side

- Diarrhea, which often tricks parents into thinking it’s just a stomach bug

The really concerning part? Perforation rates in young children run much higher, reaching 30 to 40 percent in kids under five. That happens because their symptoms are harder to spot and diagnosis gets delayed.

The Pregnant Woman’s Challenge:

Pregnancy makes appendicitis trickier to catch for two reasons. First, everyday pregnancy symptoms like nausea, vomiting, and belly discomfort look a lot like early appendicitis. Second, the growing uterus physically pushes the appendix upward as the pregnancy progresses.

By the third trimester, appendicitis pain might show up in the upper right abdomen or even near the rib cage, not in the classic lower right location at all.

Doctors typically use ultrasound first for pregnant patients because it doesn’t involve radiation. If those results aren’t clear, MRI works as a safe backup. A delayed diagnosis during pregnancy puts both mother and baby at risk, including the chance of preterm labor and fetal loss.

Why Elderly Patients Face Greater Danger:

Older adults are especially vulnerable because their immune systems don’t react as strongly. An elderly person with appendicitis might not run a significant fever or show the kind of dramatic tenderness younger patients do. Their pain may be mild and spread out. Their white blood cell counts might barely budge.

That muted response means elderly patients more often show up at the hospital with advanced-stage appendicitis already in progress. Mortality rates jump considerably after age 80, particularly when heart disease, diabetes, or other conditions are part of the picture.

How Doctors Figure Out Your Risk: Scoring System Worth Knowing About

When you show up at the emergency room with belly pain, doctors don’t rely on guesswork. They use structured scoring systems to figure out how likely it is that appendicitis is the culprit.

The Alvarado Score:

This system, sometimes remembered by the mnemonic “MANTRELS,” combines your symptoms, exam findings, and lab results into a number out of 10.

You earn points for:

- Pain that has moved to the right lower quadrant

- Loss of appetite

- Nausea or vomiting

- Tenderness in the right lower quadrant

- Rebound tenderness

- Elevated body temperature

- High white blood cell count

- A leftward shift in white blood cell types

A score of 5 or 6 means appendicitis is possible and needs more investigation. Hit 7 or above, and surgery is often the next step.

The AIR Score:

The Appendicitis Inflammatory Response Score is a newer tool that leans more heavily on lab results.

It looks at:

- Right lower quadrant pain or tenderness

- Vomiting

- White blood cell count

- The proportion of neutrophils in your blood

- C-reactive protein (CRP) levels

Scores run from 0 to 12. What makes this tool especially helpful is that it can separate low-risk patients who are safe to observe from high-risk patients who need surgery right away.

Neither scoring system is perfect on its own. But when doctors combine them with imaging, whether that’s a CT scan, ultrasound, or MRI, they can reduce unnecessary surgeries and catch real cases before things get out of hand.

What to Do When You Suspect Appendicitis

Most articles about appendicitis tell you what happens inside your body, but they skip the practical part. What should you actually do during those critical hours between “something feels off” and “I’m being wheeled into surgery”? Here’s a breakdown.

Vague Pain Around the Belly Button

This is where most people hesitate. The pain is mild and could be anything.

What you should do:

- Stop eating and drinking. If you end up needing surgery, an empty stomach makes anesthesia safer and the procedure smoother

- Don’t take laxatives or put a heating pad on your belly. Both can make things worse if your appendix is inflamed

- Skip the ibuprofen or other painkillers. They can mask your symptoms and make it harder for doctors to figure out what’s going on

- If the pain sticks around for more than two or three hours, or if it starts moving, go to the emergency room

Hours 6 to 12: Pain Settling Into the Lower Right Side

By now, the pattern is clearer. The pain has focused, it’s stronger, and you probably feel nauseous or have a low fever.

What you should do:

- Don’t drive yourself. The pain can spike suddenly and make driving dangerous.

- Have someone take you, or call for emergency transport.

- When you get to the ER, tell the doctor exactly when the pain started, where it began, and how it’s changed since then. That information feeds directly into the scoring systems they use.

- Expect a physical exam, blood work checking your white blood cell count and CRP, and most likely some kind of imaging.

Final Thought

The 4 stages of appendicitis, from early inflammation to suppurative infection to gangrene to perforation, move faster than most people expect. What feels like mild indigestion at breakfast can turn into a life-threatening emergency by dinner. If your belly pain starts out vague and then zeroes in on the lower right side, especially with nausea, fever, or pain that gets worse when you move, your body is waving a red flag. Listen to it. An early trip to the emergency room might eat up a few hours of your day, but ignoring those warning signs could cost you a whole lot more.