Understanding Levoscoliosis of the Lumbar Spine

When your doctor mentions “levoscoliosis of the lumbar spine,” it can sound intimidating. Breaking down the terminology makes it much clearer: “levo” means left, “scoliosis” refers to an abnormal sideways curvature and rotation of the spine, and “lumbar” describes the lower back region. In simple terms, this condition involves a spinal curve that bends toward the left side in your lower back.

The peculiarity of this very presentation is its unusual character. In the majority of the cases of scoliosis, there is a curve that turns to the right (dextroscoliosis) especially in the thoracic or mid-back area. When the spine folds on left, rather, the clinicians will probe more into the underlying causes.

The Anatomy of Scoliosis

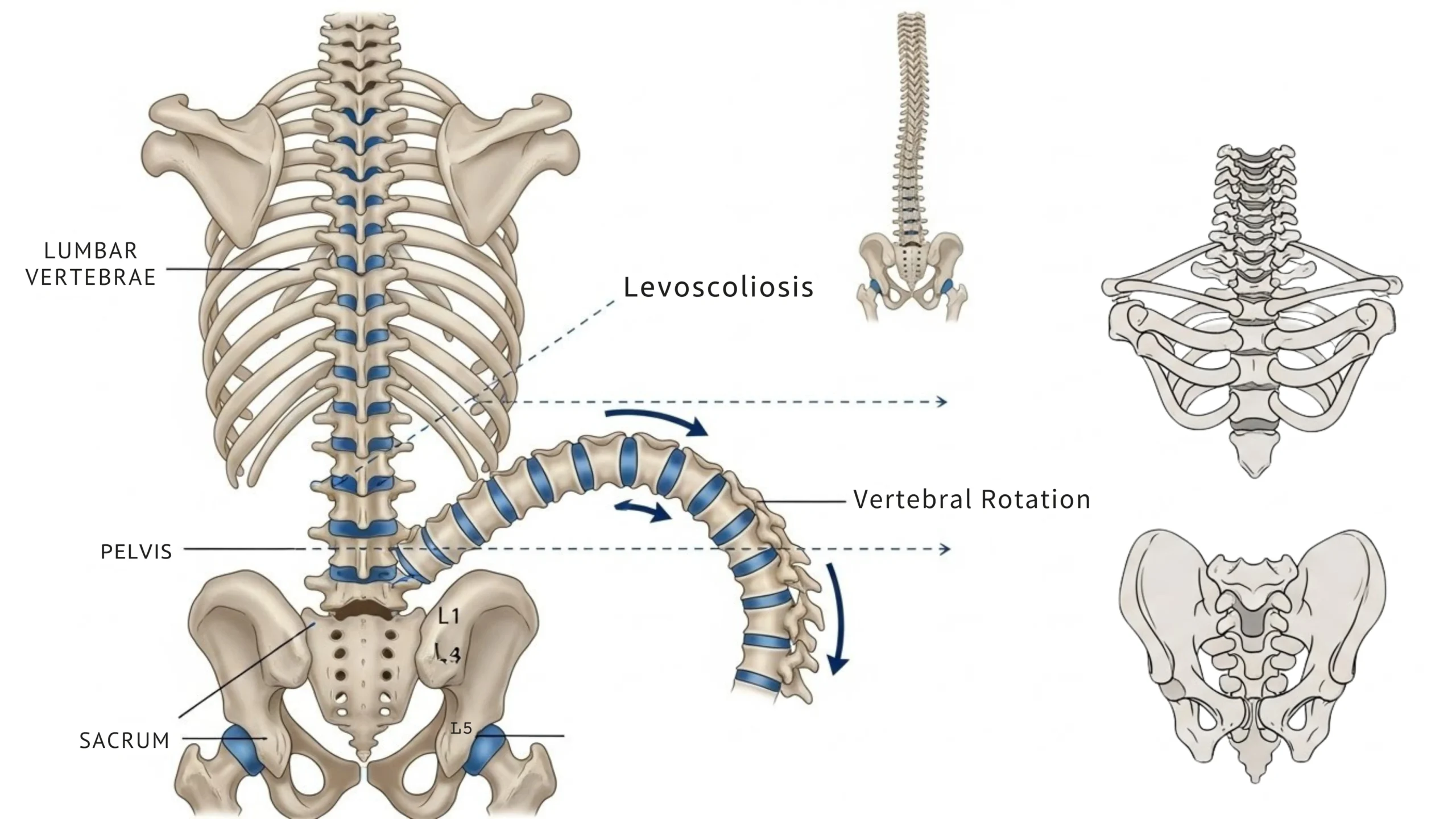

A healthy spine viewed from behind should appear relatively straight. However, the spine naturally has gentle curves when viewed from the side these front-to-back curves help with shock absorption and weight distribution during movement. Scoliosis introduces an additional side-to-side curvature that shouldn’t exist.

What distinguishes scoliosis from a simple postural lean is its three-dimensional nature. The spine doesn’t just bend sideways; it also rotates, twisting the vertebrae along the spinal axis. This rotation can cause the ribs on one side to become more prominent and may affect the spaces between vertebrae, potentially compressing structures within the spinal column.

To get a diagnosis of scoliosis, the Cobb angle that is measured in the X-ray imaging must be 10 degrees and above. Dr. This technique of measuring spinal curvature severity was developed by John R. Cobb in the year 1948 and has been used up to date. The curves with a range between 10-25 are mild, between 25-45 are moderate whereas above 45 are severe.

How Common Is Scoliosis

Scoliosis affects a significant portion of the population. A 2024 systematic review and meta-analysis published in Frontiers in Pediatrics analyzed 32 studies covering over 55 million children and adolescents, finding an overall prevalence rate of 3.1% for scoliosis (Frontiers in Pediatrics, 2024). The prevalence was higher in females (4.06%) compared to males (2.58%).

Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis represents the most common form, typically appearing during the growth spurt before puberty, around ages 10 to 15. Approximately 80% of all scoliosis cases are classified as idiopathic, meaning the cause remains unknown.

Why Does Left-Bending Matter

The direction of a scoliotic curve carries diagnostic significance. Right-bending curves (dextroscoliosis) in the thoracic spine are considered typical, particularly in idiopathic cases. Left-bending curves, however, are considered atypical and may signal an underlying condition that warrants investigation.

When physicians encounter levoscoliosis, they often explore potential causes including neuromuscular conditions affecting communication between the brain and spinal muscles, congenital abnormalities present from birth involving vertebral malformation, degenerative changes in the spine occurring with age, and traumatic injuries to the spine including tumors.

This doesn’t mean every case of levoscoliosis has a serious underlying cause many remain idiopathic. However, the atypical curve direction prompts clinicians to be thorough in their evaluation.

Signs and Symptoms

The symptoms of lumbar levoscoliosis vary considerably based on curve severity and individual factors. Mild cases often produce no noticeable symptoms and may only be discovered during routine physical examinations or screening programs.

As curves progress or in more severe cases, people may experience visible changes in posture such as uneven hips or shoulders and a noticeable sideways lean. Lower back pain and stiffness become more common in adults with scoliosis, and the irregular spinal alignment may cause muscle fatigue as surrounding muscles work harder to compensate for the abnormal curvature.

In significant cases, the curved spine can narrow the spaces through which nerves exit, potentially causing radicular symptoms. These may include pain, numbness, or tingling that radiates into the hips, buttocks, or legs. Spinal stenosis narrowing of the spinal canal can accompany progressive scoliosis and cause symptoms such as leg cramping or weakness during walking. These symptoms typically improve when sitting or bending forward, as these positions temporarily increase space within the spinal canal.

Diagnosis Process

Diagnosis begins with a thorough physical examination. The physician will observe posture from multiple angles, looking for asymmetries in shoulder height, hip alignment, and the prominence of the shoulder blades or ribs. The Adam’s Forward Bend Test where the patient bends forward at the waist while the examiner observes the back from behind can reveal rotational deformities that indicate scoliosis.

A scoliometer may be used during this test to measure trunk rotation. If clinical findings suggest scoliosis, imaging studies confirm the diagnosis. Standing X-rays of the entire spine allow measurement of the Cobb angle and identification of the specific vertebrae involved. MRI or CT scans may be ordered if neurological symptoms are present or if the physician suspects underlying structural abnormalities contributing to the curve.

Treatment Approaches

Treatment decisions depend on multiple factors: the patient’s age and skeletal maturity, curve severity and location, whether the curve is progressing, and the presence of symptoms.

Observation and Monitoring

For mild curves (10-25 degrees), particularly in skeletally mature individuals, regular monitoring without active intervention may be appropriate. This typically involves periodic clinical examinations and repeat imaging to track any changes over time.

Bracing

Bracing is primarily used in growing children and adolescents with moderate curves (25-45 degrees) to prevent progression during growth. The landmark BrAIST study (Bracing in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis Trial) published in the New England Journal of Medicine demonstrated that bracing significantly decreased the progression of high-risk curves to the surgical threshold, compared to observation alone (New England Journal of Medicine, 2013). The study found a strong relationship between hours of daily brace wear and successful outcomes. Common brace types include the thoracolumbosacral orthosis (TLSO), which is worn under clothing for a prescribed number of hours daily, often 16-23 hours.

Physical Therapy and Scoliosis-Specific Exercises

The Schroth method, developed by German physiotherapist Katharina Schroth in the early 20th century, represents one of the most studied approaches to scoliosis-specific exercise. This technique uses three-dimensional correction principles, combining postural awareness, specific breathing patterns, and targeted exercises tailored to each patient’s unique curve pattern.

A 2023 systematic review and meta-analysis in the Journal of Clinical Medicine found that the Schroth method in isolation was effective for reducing the Cobb angle and trunk rotation angle and improving quality of life compared to no intervention or other conservative therapies in adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis (Journal of Clinical Medicine, 2023).

The Society on Scoliosis Orthopaedic and Rehabilitation Treatment (SOSORT) recommends physiotherapeutic scoliosis-specific exercises as an important option to slow or stop curve progression. These exercises are individualized, focusing on auto-correction in three dimensions, training in activities of daily living, and stabilization of corrected posture.

Surgical Intervention

Surgery is generally considered when curves exceed 45-50 degrees in adolescents or when significant pain, functional impairment, or progression occurs despite conservative treatment. Posterior spinal fusion with instrumentation (rods and screws) remains the standard surgical approach, aiming to correct the curve and fuse the affected vertebrae to prevent further progression.

Surgical correction typically aims to reduce curvature to less than 25 degrees, though the achievable correction depends on spinal flexibility before surgery. Newer fusionless techniques like vertebral body tethering are being investigated for select patients, potentially preserving some spinal motion, though long-term outcomes are still being studied.

Surgery carries risks including infection, bleeding, and neurological complications, though serious complications are relatively uncommon in experienced centers. Intraoperative neurological monitoring helps surgeons detect and address any nerve concerns during the procedure.

Living with Lumbar Levoscoliosis

Most people with mild to moderate scoliosis lead active, normal lives. Core-strengthening exercises, regular physical activity, and attention to posture can help manage symptoms and support spinal health. Swimming, walking, and yoga are often well-tolerated activities that promote strength and flexibility without excessive spinal stress.

For adults experiencing degenerative scoliosis with associated leg symptoms, physical therapy remains a first-line treatment. Anti-inflammatory medications, epidural steroid injections, and other non-surgical approaches can effectively manage symptoms for many patients.

Regular follow-up with a spine specialist helps ensure any progression is detected early. Even curves that remained stable during adolescence can sometimes progress in adulthood, particularly after age 50 when degenerative changes may accelerate.

When to Seek Medical Attention

Consider consulting a healthcare provider if you notice uneven shoulders, hips, or waistline, one shoulder blade appearing more prominent than the other, your body leaning to one side, persistent back pain that doesn’t improve with rest, or numbness, tingling, or weakness in the legs.

Early detection allows for more treatment options and better outcomes, particularly in growing children where bracing may prevent surgical-level progression.

Conclusion

Levoscoliosis of the lumbar spine describes a leftward curvature in the lower back a presentation that, while less common than right-bending curves, responds to the same spectrum of treatment approaches. Understanding your diagnosis empowers you to participate actively in treatment decisions and implement lifestyle strategies that support spinal health.

Whether your scoliosis requires simple monitoring, physical therapy, bracing, or surgical consideration, working with knowledgeable healthcare providers ensures you receive care appropriate to your individual situation. With proper management, most people with levoscoliosis maintain excellent function and quality of life.

References

- Guo Y, et al. Prevalence of scoliosis in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Pediatrics. 2024;12:1399049.

- Weinstein SL, et al. Effects of Bracing in Adolescents with Idiopathic Scoliosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;369(16):1512-1521.

- Alanazi MH, et al. The effectiveness of Schroth method in Cobb angle, quality of life and trunk rotation angle in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023;12(10):3402.

- Horng MH, et al. Cobb Angle Measurement of Spine from X-Ray Images Using Convolutional Neural Network. Computational and Mathematical Methods in Medicine. 2019;2019:6357171.

- Negrini S, et al. Bracing In The Treatment Of Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis: Evidence To Date. Adolescent Health, Medicine and Therapeutics. 2019;10:97-108.

- Lee HS, et al. Incidence and Surgery Rate of Idiopathic Scoliosis: A Nationwide Database Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(15):8152.

- Kuznia AL, et al. Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis. StatPearls Publishing. 2023.